A Beginner’s Guide to Materials Science: Concepts, Examples, and Real-World Applications Explained

By Mufaddal Shakir

12/20/202512 min read

Introduction

Materials science is the field that explores the stuff everything is made of—metals, plastics, ceramics, composites, semiconductors, biomaterials, and beyond. Whether it’s the gorilla-glass of your mobile, the carbon‐fiber composite body of a racing car, the biodegradable cutlery at a restaurant, or the steel inside a skyscraper, materials science determines how these products perform, how long they last, and how sustainably they can be produced.

Materials science sits at the intersection of physics, chemistry, engineering, and even biology, making it one of the most interdisciplinary scientific domains. The central idea is simple yet powerful:

If you understand the structure of a material, you can predict and engineer its properties and performance.

This beginner-friendly article explains the fundamentals of materials science in a way that is simple, intuitive, and scientifically accurate.

1. What Exactly Is Materials Science?

Materials science is the study of how the structure of materials at different length scales, from the atomic to the macroscopic, affects their properties, processing, and ultimately their performance in real-world applications.

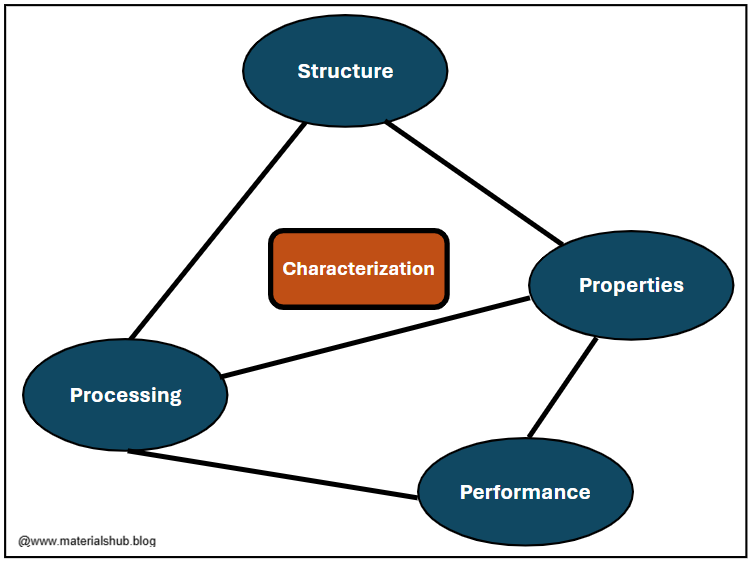

The field is often summarized by the famous Materials Science and Engineering (MSE) tetrahedron:

Structure (atomic structure, microstructure)

Properties (mechanical, thermal, chemical, electrical, optical)

Processing (manufacturing techniques)

Performance (how the material behaves in real-world use)

For example:

Adding carbon to iron changes its structure and forms steel, thereby making it stronger and tougher.

Stretching a polymer aligns its chains, which increases its toughness.

Heating and slowly cooling an alloy alters its microstructure, thereby improving its ductility.

Structure, Properties, Processing, and Performance Tetrahedron

2. Why Do We Need Materials Science?

Modern technology depends not just on design, but on having the right material for the job. The U.S National Academy of Engineers (NAE), with a diverse committee of experts from around the world, some of the most accomplished engineers and scientists of their generation, have proposed 14 grand challenges for engineering:

Make Solar Energy Economical

Provide Energy from Fusion

Develop Carbon Sequestration Methods

Manage the Nitrogen Cycle

Provide Access to Clean Water

Restore and Improve Urban Infrastructure

Advance Health Informatics

Engineer Better Medicines

Reverse Engineer the Brain

Prevent Nuclear Terror

Secure Cyberspace

Enhance Virtual Reality

Advance Personalized Learning

Engineer the Tools of Scientific Discovery

From energy and environment to health and cybersecurity, new materials drive breakthroughs by offering superior strength, conductivity, biocompatibility, and functionality, thus tackling these complex global challenges.

Also, materials science helps answer questions like:

What material is strong enough for aircrafts yet light-weight to save fuel?

Which material is capable of withstanding high-temperature inside a car engine?

What material allows a smartphone battery to last longer?

How can we create materials that degrade naturally instead of harming the environment?

Every breakthrough, from electric vehicles to quantum computers, requires new or improved materials.

3. The Structure of Materials

Understanding the structure of material is important because it defines a material's properties (strength, conductivity, etc.), which in turn determines its function, performance, and application, enabling material scientists to tailor materials for specific uses, from strong alloys for aircrafts to flexible polymers for electronics, ensuring safety, efficiency, and innovation. It bridges the gap between atomic-level arrangements and real-world behaviour, allowing for the development of innovative materials with desired properties. Material structure exists at multiple levels:

a) Atomic Structure

This includes:

Atoms and how they are arranged

Chemical bonds (ionic, covalent, metallic, van der Waals)

Lattice structures in crystals

Atomic structure determines basic material categories:

Metals → metallic bonds → conductive and ductile

Ceramics → ionic/covalent bonds → hard and brittle

Polymers → covalent chains → flexible or rubbery

Composites → combination → tailored properties

b) Microstructure

Microstructure includes:

Grains

Grain boundaries

Crystal defects

Pores

Fibers and particles in composites

Even if two materials have the same composition, their microstructure can greatly change their properties. Heat treatments, cooling rates, and processing methods influence microstructure.

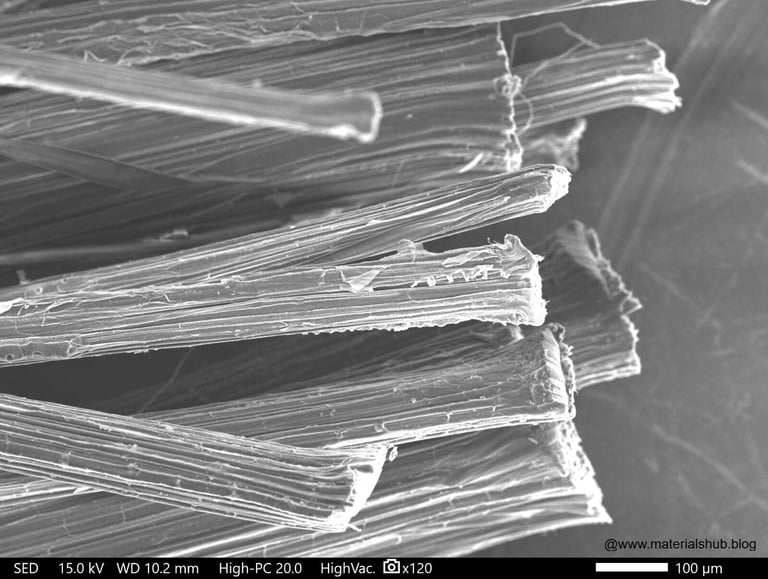

c) Macrostructure

What we can see with our naked eye:

Layers in laminated composites

Surface finishes

Coatings

Textures

Microstructure of natural fibers at ×100 magnification

4. Properties of Materials

Understanding the properties of materials is important for selecting the right substance for a job, ensuring performance, safety, and cost-effectiveness by knowing how materials react to forces, temperature, electricity, and chemicals, which guides everything from designing a car (requiring strength) to making a cooking pan (needing conductivity). It allows materials scientists to predict the behaviour, optimize manufacturing process, prevent failures, and develop new products, directly affecting product quality, function, and environmental impact. Some major categories:

Mechanical properties

Tensile Strength: The maximum stress a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before it fractures or breaks. The tensile strength indicates the ultimate load-bearing capacity of a material.

Yield Strength: The stress at which a material undergoes permanent, plastic deformation, meaning that once the load is removed, the material will not return back to its original shape or size.

Flexural Strength: A material's ability to resist bending forces. It is also sometimes referred to as bending strength. Flexural strength is calculated by applying force to the center of a material supported at both ends, causing the material to bend.

Compressive Strength: A material's ability to withstand being crushed or pushed together. Compressive strength is measured by applying a uniform force to the entire surface. Materials generally have a higher compressive strength than flexural strength.

Impact Strength: It is the ability of a material to withstand a sudden, high-speed load or shock without fracturing. Impact strength tells us how much energy a material can absorb before it breaks.

Young's Modulus: It is a measure of a material's rigidity that indicates its resistance to elastic deformation under tensile or compressive stress. It is also referred to as elastic modulus and is calculated as the ratio of stress to strain. A higher value of Young's modulus signifies a stiffer material that is less likely to stretch or compress.

Toughness: It is the ability of a material to absorb energy and deform plastically without fracturing when subjected to stress or impact. In order to have good toughness, a material must be both strong and ductile.

Hardness: It is the resistance of a material to localized plastic deformation, which can be caused by indentation, scratching, or abrasion. Hardness tells about a material's durability and capability to withstand wear and penetration.

Fatigue Strength: It is the highest stress a material can withstand for a specific number of load cycles before it fails. It shows how much stress a material can endure without breaking due to repeated stress cycles, a critical property for components in industries like aviation and automobile, where components are subject to cyclic loading.

Creep: It is a material's ability to resist permanent deformation over time under a constant load, especially at high temperatures. Creep is a slow, permanent deformation that occurs under sustained stress, even if that stress is below the material's yield strength.

Thermal properties

Melting point: It is a specific temperature at which a material changes from solid to liquid state when heat is applied to it. During the melting process, the temperature stays constant until all the solid has turned into a liquid. A high melting point indicates that strong forces (like ionic bonds) hold the particles together, needing more energy to break the bonds.

Thermal conductivity: It is the ability of a material to conduct heat, telling how quickly heat transfers through it when there is a temperature difference. A high thermal conductivity value means fast transfer of heat, whereas low thermal conductivity means slow transfer of heat. This property depends upon the structure, phase, density, and composition of a material.

Heat capacity: It is the amount of heat energy required to raise the temperature of a substance by one degree (Celsius or Kelvin), representing the ability of a material to store thermal energy. It is an extensive property and depends on the mass or size of a material.

Thermal expansion: It is the tendency of matter to increase in length, area, or volume, changing its size and density, in response to an increase in temperature. It is an important property that helps in designing material by preventing damage from temperature changes.

Electrical properties

Electrical conductivity: It is the ability of a material to allow electric current to flow through it. Materials having high conductivity (metals such as silver and copper) allow easy flow of electrons, and materials with low conductivity (plastics and glass) have poor flow of electrons.

Resistivity: It is an intrinsic property that defines how strongly a material resists electric current per unit length and area. Metals such as copper have low resistivity (good conductors), while some plastics and rubber have high resistivity (insulators).

Dielectric behaviour: It describes how an insulator (dielectric) responds to an electric field by polarizing—its internal charges shift to create opposing internal fields, storing energy and reducing the overall field, rather than conducting current. This property, measured by the dielectric constant, tells us how much energy a material stores (like in a capacitor) and how it interacts with electromagnetic waves, which is important for insulation, energy storage, and electronics.

Optical properties

Transparency: It is the ability of a material to let light pass through it without significant scattering, allowing objects behind it to be seen clearly, for example, clear glass, water, and some specific crystals or polymers. Materials may be classified as transparent, having a clear view; translucent, having some scattering giving a blurry view; or opaque, meaning the view is blocked as no light passes. A uniform molecular arrangement (like in some polymer films) promotes transparency, while grain boundaries or defects cause scattering.

Reflectivity: It measures how much incident light or electromagnetic energy gets reflected back, expressed as a percentage or fraction of the total energy hitting its surface, depending on factors like the type of material, surface roughness, and wavelength. Materials having high reflectivity send back most of the light, while materials with low reflectivity absorb more.

Refractive index: It is the ratio of the speed of light in a vacuum (or air) to the speed of light in a transparent material, and it tells about how light bends when passing through different mediums. A higher value of refractive index means that light travels slower and bends more, with diamond being able to bend light more than water. This property is essential for designing prisms, lenses, and optical fibers.

Chemical properties

Corrosion resistance: It is the ability of a material to withstand degradation from chemical reactions with its environment, such as oxidation, without corroding or losing its integrity. Materials having high corrosion resistance are used in applications where longevity and safety are important.

Oxidation behaviour: It tells how a material reacts with oxygen and other oxidizing agents, leading to chemical and physical changes like corrosion or the formation of oxide layers. It is influenced by factors such as temperature, oxygen pressure, the material's chemical composition, and its microstructure.

Reactivity: It is the tendency of a material to undergo a chemical reaction with another substance. It indicates how easily a material can participate in a chemical transformation, often with a release of energy. Factors like temperature, pressure, surface area, and chemical purity influence how reactive a material is.

Biological properties

Biocompatibility: It is the ability of a material to interact with a biological system without causing a harmful or toxic response. It is an important property for medical devices and biomaterials, ensuring they can perform their intended function without getting an adverse local or systemic reaction from the body.

Degradability: It is the capacity of a material to break down into smaller components over time by means of chemical or biological processes. Degradability is important for understanding a material's life period, performance, and environmental impact.

Materials scientists study how the structure of a material affects each of these properties. Having good knowledge of properties helps in the development of new materials and improved designs, enabling advancements in technology.

Comparison of properties between metals, ceramics, and polymers

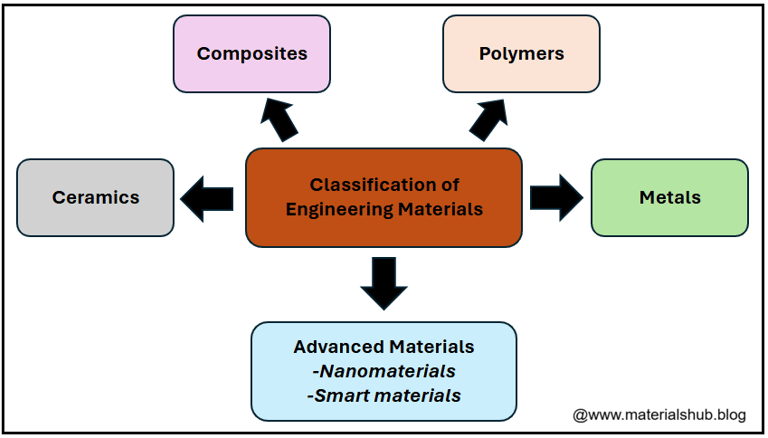

5. The Four Major Classes of Materials

1. Metals

Metals are excellent conductors of both heat and electricity. For example, copper is used for electrical wiring because of its high conductivity.

Metals are ductile, that is, they have the ability to be drawn into thin wires, and malleable, that is, they can be pressed into thin sheets without breaking.

They are known to possess high strength, hardness, and toughness.

Metals generally have high melting and boiling points and are solid at room temperature.

They are extensively used in the automotive, aerospace, construction, and electronics industries.

2. Ceramics

Ceramics have low electrical and thermal conductivity and possess excellent electrical insulation properties.

They have exceptionally high hardness and high strength, especially in compression.

Their hardness makes them very resistant to scratching, abrasion, and wear.

Ceramics have high melting points, which makes them a perfect candidate for high-temperature applications.

Ceramics are mostly used in aerospace, construction, electronics, and medical industries.

3. Polymers

Unlike metals and ceramics, polymers are flexible and lightweight in nature.

Polymers are excellent electrical and thermal insulators.

Polymers generally have a high strength-to-weight ratio.

They can be easily molded and processed into complex components.

They are commonly used in packaging, automotive parts, electronics, textiles, and medical fields.

4. Composites

Composites are made of two or more materials.

They offer superior mechanical properties, usually outperforming metals for the same weight.

They have high resistance to corrosion, wear, and fatigue, leading to longer lifespans and reduced maintenance.

Composite materials can be engineered for specific applications, such as achieving specific strength and stiffness, matching thermal properties, or controlling electrical conductivity.

Their high strength-to-weight ratio allows for lighter, more fuel-efficient structures in aerospace, automotive, sporting equipment, construction, and other fields.

5. Advanced and Emerging Materials

Nanomaterials have unique properties because of their small size (typically in the range of 1 to 100 nm), including a high surface-to-volume ratio, superior mechanical properties, unique optical and electrical characteristics, and increased chemical reactivity. These properties make them useful for applications in medicine, electronics, and energy storage, as their behaviour is governed by quantum mechanics rather than classical physics. Examples include carbon nanotubes, nanofibers, and nanoparticles (like gold, silver, titanium, etc.).

Smart materials are characterized by their ability to respond to external stimuli such as light, heat, or pressure by changing their properties in a controlled and often reversible way. Key characteristics include responsiveness, self-regulation, durability, and adaptability. These materials are also capable of changing properties like shape, colour, or stiffness. Some examples include shape memory alloys, self-healing materials, and smart polymers.

Classification of engineering materials

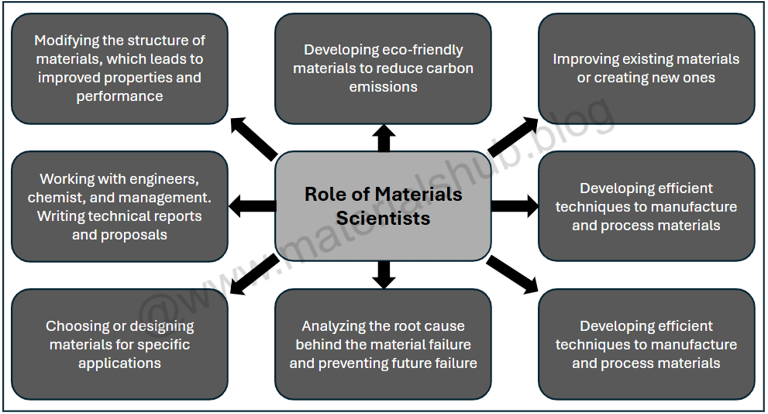

6. What Do Materials Scientists Actually Do?

Materials scientists play a crucial role in technological advancement by researching and creating materials such as metals, ceramics, polymers, and advanced composites that have excellent properties for utilization in industries such as automotive, aerospace, marine, construction, medicine, and electronics. Materials scientists work on analyzing the structure (atomic, micro, and macro), properties (mechanical, thermal, chemical, and electrical), processing routes, and performance of the materials, then testing and employing them for real-world applications. Their role often involves research, design, testing, and collaboration by improving the already existing materials or developing new ones. Materials scientists often work on:

Improving existing materials and developing new alloys, ceramics, polymers, and advanced composite materials to meet the performance requirements.

Developing environmentally friendly materials in order to minimize pollution, improving recycling, and reducing material waste.

Analyzing the properties of materials and ensuring that materials are strong, durable, and able to resist the real-world environmental conditions.

Designing and improving manufacturing processes (like casting, injection molding, and 3D printing) to control the structure of materials and enhance their performance.

Analyzing the reason behind the failure of materials and providing solutions to prevent their failure in the future.

Materials scientists guide product development across various industries, such as automotive, aerospace, energy, biomedical, construction, and electronics.

Key roles and responsibilities of a materials scientist

7. How Materials Science Shapes the Real World

Materials science shapes our world by designing, analyzing, and developing new materials that drive innovation across different industrial sectors, from creating electronics smaller and batteries better and lighter to making medical devices, stronger and tougher aerospace parts, and eco-friendly solutions for energy and the environment, mainly acting as the foundation for modern technology. Following are some examples of the latest advancements of materials science in various industries:

Electronics

Usage of magnetic materials such as Heusler alloys or CoFeB (Cobalt-Iron-Boron) alloys for non-volatile memory (MRAM) and data storage applications.

SiC-based materials (patent filed by Huawei) providing improved thermal conduction and electromagnetic interference (EMI) management for high-performance AI and power electronics.

Utilization of advanced nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, and quantum dots in supercapacitors, sensors, transistors, and printable circuits.

Automotive

Lightweight carbon fiber-reinforced composite body panels in luxury and Formula 1 racing cars.

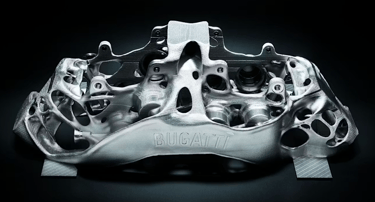

World's first 3D-printed titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) and largest brake caliper in the automotive industry for Bugatti Chiron.

Development of sustainable bamboo fiber-reinforced composites by IIT Guwahati for automotive interior components.

Use of magnesium and aluminium alloys for EV battery enclosures and mounting frames for reducing battery weight and improving efficiency.

Aerospace

Utilization of carbon fiber-reinforced composites for wings, fuselage, and structural parts in the Airbus A350 and Boeing 787 Dreamliner, offering superior strength and reducing aircraft weight, thus improving fuel efficiency.

3D-printed aluminium and titanium alloys for critical structural and low-volume aerospace parts, reducing material waste and producing components with complex geometries not possible with conventional machining.

Ceramic coatings for thermal protection on re-entry vehicles and hypersonic aircraft due to their thermal stability at high temperatures.

Structural battery composites that combine mechanical integrity with energy storage are being explored for future aircraft and space systems.

Energy

Utilization of perovskite solar cells in the solar technology offering higher energy efficiency and showing potential for lightweight and low-cost solar panels.

High Entropy Alloys for hydrogen storage and fuel cell catalysts, providing better stability in comparison to traditional metals.

Commercialization of a low-cost and highly efficient thermal battery using solid carbon blocks as a storage medium by Antora Energy.

Medical

3D-printed orthopedic implants or stents made from titanium or biocompatible polymers.

Usage of nanocomposite hydrogels to mimic tissue scaffolds and enable controlled drug release.

Utilization of Bioglass 45S5 in jaw and orthopedic applications, as it can dissolve and stimulate the natural bone to repair itself.

3D-printed titanium brake caliper (Source: Bugatti)

Conclusion

Materials science is the foundation on which modern engineering is built. It helps us understand how the arrangement of atoms translates into real-world performance and enables the design of stronger, lighter, efficient, and more sustainable materials.

For beginners, the field may seem broad, but its beauty lies in its simplicity:

Change the structure → Change the properties → Engineer the material you want.

References:

1. Callister Jr, W. D., & Rethwisch, D. G. (2020). Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons.

2. González-Viñas, W., & Mancini, H. L. (2004). An Introduction to Materials Science. Princeton University Press.

3. Brostow, W., & Lobland, H. E. H. (2016). Materials: Introduction and Applications. John Wiley & Sons.

4. Behera, A. (2021). Advanced materials: An Introduction to Modern Materials Science. Springer Nature.

5. Askeland, D. R., Phulé, P. P., Wright, W. J., & Bhattacharya, D. K. (2003). The Science and Engineering of Materials. Springer Nature.

Contact

© 2026. MaterialsHub. All rights reserved.